Why ‘Black Panther’ Is a Defining Moment for Black America

The Grand Lake Theater — the kind of old-time movie house with cavernous ceilings and ornate crown moldings — is one place I take my kids to remind us that we belong to Oakland, Calif. Whenever there is a film or community event that has meaning for this town, the Grand Lake is where you go to see it. There are local film festivals, indie film festivals, erotic film festivals, congressional town halls, political fund-raisers. After Hurricane Katrina, the lobby served as a drop-off for donations. We run into friends and classmates there. On weekends we meet at the farmers’ market across the street for coffee.

The last momentous community event I experienced at the Grand Lake was a weeknight viewing of “Fruitvale Station,” the 2013 film directed by the Bay Area native Ryan Coogler. It was about the real-life police shooting of Oscar Grant, 22, right here in Oakland, where Grant’s killing landed less like a news story and more like the death of a friend or a child. He had worked at a popular grocery, gone to schools and summer camps with the children of acquaintances. His death — he was shot by the transit police while handcuffed, unarmed and face down on a train-station platform, early in the morning of New Year’s Day 2009 — sparked intense grief, outrage and sustained protest, years before Black Lives Matter took shape as a movement. Coogler’s telling took us slowly through the minutiae of Grant’s last day alive: We saw his family and child, his struggles at work, his relationship to a gentrifying city, his attempts to make sense of a young life that felt both aimless and daunting. But the moment I remember most took place after the movie was over: A group of us, friends and strangers alike and nearly all black, stood in the cool night under the marquee, crying and holding one another. It didn’t matter that we didn’t know one another. We knew enough.

On a misty morning this January, I found myself standing at that same spot, having gotten out of my car to take a picture of the Grand Lake’s marquee. The words “Black Panther” were on it, placed dead center. They were not in normal-size letters; the theater was using the biggest ones it had. All the other titles huddled together in another corner of the marquee. A month away from its Feb. 16 opening, “Black Panther” was, already and by a wide margin, the most important thing happening at the Grand Lake.

Marvel Comics’s Black Panther was originally conceived in 1966 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, two Jewish New Yorkers, as a bid to offer black readers a character to identify with. The titular hero, whose real name is T’Challa, is heir apparent to the throne of Wakanda, a fictional African nation. The tiny country has, for centuries, been in nearly sole possession of vibranium, an alien element acquired from a fallen meteor. (Vibranium is powerful and nearly indestructible; it’s in the special alloy Captain America’s shield is made of.) Wakanda’s rulers have wisely kept their homeland and its elemental riches hidden from the world, and in its isolation the nation has grown wildly powerful and technologically advanced. Its secret, of course, is inevitably discovered, and as the world’s evil powers plot to extract the resources of yet another African nation, T’Challa’s father is cruelly assassinated, forcing the end of Wakanda’s sequestration. The young king will be forced to don the virtually indestructible vibranium Black Panther suit and face a duplicitous world on behalf of his people.

This is the subject of Ryan Coogler’s third feature film — after “Fruitvale Station” and “Creed” (2015) — and when glimpses of the work first appeared last June, the response was frenzied. The trailer teaser — not even the full trailer — racked up 89 million views in 24 hours. On Jan. 10, 2018, after tickets were made available for presale, Fandango’s managing editor, Erik Davis, tweeted that the movie’s first 24 hours of advance ticket sales exceeded those of any other movie from the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

The black internet was, to put it mildly, exploding. Twitter reported that “Black Panther” was one of the most tweeted-about films of 2017, despite not even opening that year. There were plans for viewing parties, a fund-raiser to arrange a private screening for the Boys & Girls Club of Harlem, hashtags like #BlackPantherSoLit and #WelcomeToWakanda. When the date of the premiere was announced, people began posting pictures of what might be called African-Americana, a kitsch version of an older generation’s pride touchstones — kente cloth du-rags, candy-colored nine-button suits, King Jaffe Joffer from “Coming to America” with his lion-hide sash — alongside captions like “This is how I’ma show up to the Black Panther premiere.” Someone described how they’d feel approaching the box office by simply posting a video of the Compton rapper Buddy Crip-walking in front of a Moroccan hotel.

None of this is because “Black Panther” is the first major black superhero movie. Far from it. In the mid-1990s, the Damon Wayans vehicle “Blankman” and Robert Townsend’s “The Meteor Man” played black-superhero premises for campy laughs. Superheroes are powerful and beloved, held in high esteem by society at large; the idea that a normal black person could experience such a thing in America was so far-fetched as to effectively constitute gallows humor. “Blade,” released in 1998, featured Wesley Snipes as a Marvel vampire hunter, and “Hancock” (2008) depicted Will Smith as a slacker antihero, but in each case the actor’s blackness seemed somewhat incidental.

“Black Panther,” by contrast, is steeped very specifically and purposefully in its blackness. “It’s the first time in a very long time that we’re seeing a film with centered black people, where we have a lot of agency,” says Jamie Broadnax, the founder of Black Girl Nerds, a pop-culture site focused on sci-fi and comic-book fandoms. These characters, she notes, “are rulers of a kingdom, inventors and creators of advanced technology. We’re not dealing with black pain, and black suffering, and black poverty” — the usual topics of acclaimed movies about the black experience.

In a video posted to Twitter in December, which has since gone viral, three young men are seen fawning over the “Black Panther” poster at a movie theater. One jokingly embraces the poster while another asks, rhetorically: “This is what white people get to feel all the time?” There is laughter before someone says, as though delivering the punch line to the most painful joke ever told: “I would love this country, too.”

Ryan Coogler saw his first Black Panther comic book as a child, at an Oakland shop called Dr. Comics & Mr. Games, about a mile from the Grand Lake Theater. When I sat down with him in early February, at the Montage Hotel in Beverly Hills, I told him about the night I saw “Fruitvale Station,” and he listened with his head down, slowly nodding. When he looked up at me, he seemed to be blinking back tears of his own.

Coogler played football in high school, and between his fitness and his humble listening poses — leaning forward, elbows propped on knees — he reminds me of what might happen if a mild-mannered athlete accidentally discovered a radioactive movie camera and was gifted with remarkable artistic vision. He’s interested in questions of identity: What does it mean to be a black person or an African person? “You know, you got to have the race conversation,” he told me, describing how his parents prepared him for the world. “And you can’t have that without having the slavery conversation. And with the slavery conversation comes a question of, O.K., so what about before that? And then when you ask that question, they got to tell you about a place that nine times out of 10 they’ve never been before. So you end up hearing about Africa, but it’s a skewed version of it. It’s not a tactile version.”

Around the time he was wrapping up “Creed,” Coogler made his first journey to the continent, visiting Kenya, South Africa and the Kingdom of Lesotho, a tiny nation in the center of the South African landmass. Tucked high amid rough mountains, Lesotho was spared much of the colonization of its neighbors, and Coogler based much of his concept of Wakanda on it. While he was there, he told me, he was being shown around by an older woman who said she’d been a lover of the South African pop star Brenda Fassie. Riding along the hills with this woman, Coogler was told that they would need to visit an even older woman in order to drop off some watermelon. During their journey, they would stop occasionally to approach a shepherd and give him a piece of watermelon; each time the shepherd would gingerly take the piece, wrap it in cloth and tuck it away as though it were a religious totem. Time passed. Another bit of travel, another shepherd, another gift of watermelon. Eventually Coogler grew frustrated: “Why are we stopping so much?” he asked. “Watermelon is sacred,” he was told. “It hydrates, it nourishes and its seeds are used for offerings.” When they arrived at the old woman’s home, it turned out that she was, in fact, a watermelon farmer, but her crop had not yet ripened — she needed a delivery to help her last the next few weeks.

When I was a kid, I refused to eat watermelon in front of white people. To this day, the word itself makes me uncomfortable. Coogler told me that in high school he and his black football teammates used to have the same rule: Never eat watermelon in front of white teammates. Centuries of demonizing and ridiculing blackness have, in effect, forced black people to abandon what was once sacred. When we spoke of Africa and black Americans’ attempts to reconnect with what we’re told is our lost home, I admitted that I sometimes wondered if we could ever fully be part of what was left behind. He dipped his head, fell briefly quiet and then looked back at me with a solemn expression. “I think we can,” he said. “It’s no question. It’s almost as if we’ve been brainwashed into thinking that we can’t have that connection.”

“Black Panther” is a Hollywood movie, and Wakanda is a fictional nation. But coming when they do, from a director like Coogler, they must also function as a place for multiple generations of black Americans to store some of our most deeply held aspirations. We have for centuries sought to either find or create a promised land where we would be untroubled by the criminal horrors of our American existence. From Paul Cuffee’s attempts in 1811 to repatriate blacks to Sierra Leone and Marcus Garvey’s back-to-Africa Black Star shipping line to the Afrocentric movements of the ’60s and ’70s, black people have populated the Africa of our imagination with our most yearning attempts at self-realization. In my earliest memories, the Africa of my family was a warm fever dream, seen on the record covers I stared at alone, the sun setting over glowing, haloed Afros, the smell of incense and oils at the homes of my father’s friends — a beauty so pure as to make the world outside, one of car commercials and blond sitcom families, feel empty and perverse in comparison. As I grew into adolescence, I began to see these romantic visions as just another irrelevant habit of the older folks, like a folk remedy or a warning to wear a jacket on a breezy day. But by then my generation was building its own African dreamscape, populated by KRS-One, Public Enemy and Poor Righteous Teachers; we were indoctrinating ourselves into a prideful militancy about our worth. By the end of the century, “Black Star” was not just the name of Garvey’s shipping line but also one of the greatest hip-hop albums ever made.

Never mind that most of us had never been to Africa. The point was not verisimilitude or a precise accounting of Africa’s reality. It was the envisioning of a free self. Nina Simone once described freedom as the absence of fear, and as with all humans, the attempt of black Americans to picture a homeland, whether real or mythical, was an attempt to picture a place where there was no fear. This is why it doesn’t matter that Wakanda was an idea from a comic book, created by two Jewish artists. No one knows colonization better than the colonized, and black folks wasted no time in recolonizing Wakanda. No genocide or takeover of land was required. Wakanda is ours now. We do with it as we please.

Until recently, most popular speculation on what the future would be like had been provided by white writers and futurists, like Isaac Asimov and Gene Roddenberry. Not coincidentally, these futures tended to carry the power dynamics of the present into perpetuity. Think of the original “Star Trek,” with its peaceful, international crew, still under the charge of a white man from Iowa. At the time, the character of Lieutenant Uhura, played by Nichelle Nichols, was so vital for African-Americans — the black woman of the future as an accomplished philologist — that, as Nichols told NPR, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself persuaded her not to quit the show after the first season. It was a symbol of great progress that she was conceived as something more than a maid. But so much still stood in the way of her being conceived as a captain.

The artistic movement called Afrofuturism, a decidedly black creation, is meant to go far beyond the limitations of the white imagination. It isn’t just the idea that black people will exist in the future, will use technology and science, will travel deep into space. It is the idea that we will have won the future. There exists, somewhere within us, an image in which we are whole, in which we are home. Afrofuturism is, if nothing else, an attempt to imagine what that home would be. “Black Panther” cannot help being part of this. “Wakanda itself is a dream state,” says the director Ava DuVernay, “a place that’s been in the hearts and minds and spirits of black people since we were brought here in chains.” She and Coogler have spent the past few months working across the hall from each other in the same editing facility, with him tending to “Black Panther” and her to her much-anticipated film of Madeleine L’Engle’s “A Wrinkle in Time.” At the heart of Wakanda, she suggests, lie some of our most excruciating existential questions: “What if they didn’t come?” she asked me. “And what if they didn’t take us? What would that have been?”

Afrofuturism, from its earliest iterations, has been an attempt to imagine an answer to these questions. The movement spans from free-jazz thinkers like Sun Ra, who wrote of an African past filled with alien technology and extraterrestrial beings, to the art of Krista Franklin and Ytasha Womack, to the writers Octavia Butler, Nnedi Okorafor and Derrick Bell, to the music of Jamila Woods and Janelle Monáe. Their work, says John I. Jennings — a media and cultural studies professor at the University of California, Riverside, and co-author of “Black Comix Returns” — is a way of upending the system, “because it jumps past the victory. Afrofuturism is like, ‘We already won.’ ” Comic books are uniquely suited to handling this proposition. In them the laws of our familiar world are broken: Mild-mannered students become godlike creatures, mutants walk among us and untold power is, in an instant, granted to the most downtrodden. They offer an escape from reality, and who might need to escape reality more than a people kidnapped to a stolen land and treated as less-than-complete humans?

At the same time, it is notable that despite selling more than a million books and being the first science-fiction author to win a MacArthur fellowship, Octavia Butler, one of Afrofuturism’s most important voices, never saw her work transferred to film, even as studios churned out adaptations of lesser works on a monthly basis. Butler’s writing not only featured African-Americans as protagonists; it specifically highlighted African-American women. If projects by and about black men have a hard time getting made, projects by and about black women have a nearly impossible one. In March, Disney will release “A Wrinkle in Time,” featuring Storm Reid and Oprah Winfrey in lead roles; the excitement around this female-led film does not seem to compare, as of yet, with the explosion that came with “Black Panther.” But by focusing on a black female hero — one who indeed saves the universe — DuVernay is embodying the deepest and most powerful essence of Afrofuturism: to imagine ourselves in places where we had not been previously imagined.

Can films like these significantly change things for black people in America? The expectations around “Black Panther” remind me of the way I heard the elders in my family talking about the mini-series “Roots,” which aired on ABC in 1977. A multigenerational drama based on the best-selling book in which Alex Haley traced his own family history, “Roots” told the story of an African slave kidnapped and brought to America, and traced his progeny through over 100 years of American history. It was an attempt to claim for us a home, because to be black in America is to be both with and without one: You are told that you must honor this land, that to refuse this is tantamount to hatred — but you are also told that you do not belong here, that you are a burden, an animal, a slave. Haley, through research and narrative and a fair bit of invention, was doing precisely what Afrofuturism does: imagining our blackness as a thing with meaning and with lineage, with value and place.

“The climate was very different in 1977,” the actor LeVar Burton recalled to me recently. Burton was just 19 when he landed an audition, his first ever, for the lead role of young Kunta Kinte in the mini-series. “We had been through the civil rights movement, and there were visible changes as a result, like there was no more Jim Crow,” he told me. “We felt that there were advancements that had been made, so the conversation had really sort of fallen off the table.” The series, he said, was poised to reignite that conversation. “The story had never been told before from the point of view of the Africans. America, both black and white, was getting an emotional education about the costs of slavery to our common American psyche.”

To say that “Roots” held the attention of a nation for its eight-consecutive-night run in January 1977 would be an understatement. Its final episode was viewed by 51.1 percent of all American homes with televisions, a kind of reach that seemed sure to bring about some change in opportunities, some new standing in American culture. “The expectation,” Burton says, “was that this was going to lead to all kinds of positive portrayals of black people on the screen both big and small, and it just didn’t happen. It didn’t go down that way, and it’s taken years.”

Here in Oakland, I am doing what it seems every other black person in the country is doing: assembling my delegation to Wakanda. We bought tickets for the opening as soon as they were available — the first time in my life I’ve done that. Our contingent is made up of my 12-year-old daughter and her friend; my 14-year-old son and his friend; one of my oldest confidants, dating back to adolescence; and two of my closest current friends. Not everyone knows everyone else. But we all know enough. Our group will be eight black people strong.

Beyond the question of what the movie will bring to African-Americans sits what might be a more important question: What will black people bring to “Black Panther”? The film arrives as a corporate product, but we are using it for our own purposes, posting with unbridled ardor about what we’re going to wear to the opening night, announcing the depths of the squads we’ll be rolling with, declaring that Feb. 16, 2018, will be “the Blackest Day in History.”

This is all part of a tradition of unrestrained celebration and joy that we have come to rely on for our spiritual survival. We know that there is no end to the reminders that our lives, our hearts, our personhoods are expendable. Yes, many nonblack people will say differently; they will declare their love for us, they will post Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela quotes one or two days a year. But the actions of our country and its collective society, and our experiences within it, speak unquestionably to the opposite. Love for black people isn’t just saying Oscar Grant should not be dead. Love for black people is Oscar Grant not being dead in the first place.

This is why we love ourselves in the loud and public way we do — because we have to counter his death with the very same force with which such deaths attack our souls. The writer and academic Eve L. Ewing told me a story about her partner, a professor of economics at the University of Chicago: When it is time for graduation, he makes the walk from his office to the celebration site in his full regalia — the gown with velvet panels, full bell sleeves and golden piping, the velvet tam with gold-strand bullion tassel. And when he does it, every year, like clockwork, some older black woman or man he doesn’t know will pull over, roll down their window, stop him and say, with a slow head shake and a deep, wide smile, something like: “I am just so proud of you!”

This is how we do with one another. We hold one another as a family because we must be a family in order to survive. Our individual successes and failures belong, in a perfectly real sense, to all of us. That can be for good or ill. But when it is good, it is very good. It is sunlight and gold on vast African mountains, it is the shining splendor of the Wakandan warriors poised and ready to fight, it is a collective soul as timeless and indestructible as vibranium. And with this love we seek to make the future ours, by making the present ours. We seek to make a place where we belong.

Minecraft teaches kids about tech, but there’s a gender imbalance at play

Arguments about “screen time” are likely to crop up in many households with children these holidays. As one of the best-selling digital games of all time, Minecraft will be a likely culprit.

In a recent survey of Australian adults, excessive “screen time” was rated as the top child health concern, but current time limit guidelines are not only criticised by some experts, but also not very achievable for many families.

Thankfully, more practical advice is on the way. We are starting to see research that looks beyond the number of hours spent playing to more meaningful studies about what children are actually doing in their digital playtime.

Our research contributes to this by studying the characteristics of children’s Minecraft play in Australia, shedding light on how kids access the game, assessing the social nature of play, and providing a reality check on claims of gender-neutrality.

Understanding the Minecraft phenomenon

Minecraft is as much a digital playground as it is a digital game. The player controls a character within a virtual environment that can be manipulated in various ways, with varying degrees of difficulty. There is no definitive goal and players are free to create and direct their own playful interactions with the landscape and its inhabitants – either on their own or with other players.

Since it was first officially released in 2011, more than 120 million copies of Minecraft have been sold. The game is one of the most searched terms on YouTube, and in 2016 an educational version was released for use in schools.

Despite these indications of its pervasiveness, no prior work had identified how popular it actually is with children in Australia.

Consequently, we surveyed 753 parents of children aged 3 to 12 living in Melbourne, and recently published our findings in New Media and Society, and the ACM SIGCHI Conference on Computer-Human Interaction in Play.

The results show that 53% of children aged 6 to 8, and 68% of children aged 9 to 12, are actively playing Minecraft. More than half of those play more than once per week.

It is now clear that Minecraft is no passing fad, but rather a new addition to 21st-century play repertoires. It is crucial that we form a detailed understanding of how children use the game and how this fits in with their overall “play worlds”.

Minecraft is a social activity

Reflecting the rise of the tablet computer in children’s digital play, more than 70% of children aged 3 to 8 primarily play Minecraft on a tablet. This falls to 50% in children aged 9 to 12, with a corresponding increase in PC-based play where more technologically challenging play is possible.

Despite the persistent myth that digital game play is a solitary activity, 80% of children in our sample at times played Minecraft with someone else – including siblings, friends, parents, other relatives or other players online. And nearly half most often played with someone else.

Although there is evidence that co-play between parents and children is one of the more effective ways to maximise the benefits of digital play, only 11% of parents reported ever playing Minecraft with their children.

Minecraft is not gender-neutral

Minecraft is often referred to as equally appealing to both boys and girls. The game’s creator, Notch, has claimed that “gender doesn’t exist” in Minecraft, and popular discourse commonly refers to young children’s digital play in titles like Minecraft as gender-neutral.

But our study shows that this does not appear to be reflected in actual player demographics.

We found that girls aged 3 to 12 are much less likely to play Minecraft than boys, with 54% of boys playing and only 32% of girls. This difference was greatest in younger children: 68% of boys aged six to eight in our study played Minecraft, but only 29% of girls.

This is important, because young children’s digital play is connected to the development of their confidence and literacy with digital technology.

What’s more, the players who most often play in the game’s more competitive “survival” mode are more likely to be boys. Girls are more likely to play in the game’s “creative” mode.

The research that supports campaigns like Let Toys Be Toys would suggest that this may be due to the broader marketing of digital games as “for boys”, even if Minecraft is for everyone.

The most striking gender difference was in relation to YouTube videos. While 32% of six to eight-year-old boys had watched Minecraft YouTube videos in the week prior to their parent taking the survey, only 9% of girls had. So not only is Minecraft play gendered, but so too is early immersion in the surrounding gamer culture.

Digital gaming can pave the way to careers in STEM

Children are increasingly required to bring iPads to school. The government (highlighting the benefits of STEM fields to the economy) casts the tech-savvy child a in central role in visions of “Australia’s future prosperity and competitiveness on the international stage”.

There is mounting evidence that Minecraft can be used to foster interest and skill in the kinds of areas that are relevant to STEM industry careers. And involvement with gamer culture is a likely inroad to interest in gaming and technological pursuits later on in life.

This is why the dominance of tablet play and the significant gender differences are so important. We need to look at why these differences exist and understand them in more detail.

It is only through this kind of information that we will be able to ask meaningful research questions and form advice for parents that maximises benefits of Minecraft play, while reducing any possible harms.

This work will ultimately mean that future advice is based more on the realities of children’s everyday practices and less on policing the clock.

In the meantime, we recommend checking out the “Parenting for a digital future” blog for practical tips on how to strike the right balance when it comes to managing screen time – including Minecraft play.

Minecraft teaches kids about tech, but there’s a gender imbalance at play

‘Minecraft’ Data Mining Reveals Players’ Darkest Secrets

Since Minecraft was first released in 2009, players have been building their own virtual worlds, erecting countless, giant statues of Pikachu and posting semi-obnoxious Let’s Play videos on YouTube. You’d think that by now, we would have seen everything Minecraft has to offer, but some of the game’s most personal, heartfelt, and tragic stories remain buried on dead servers.

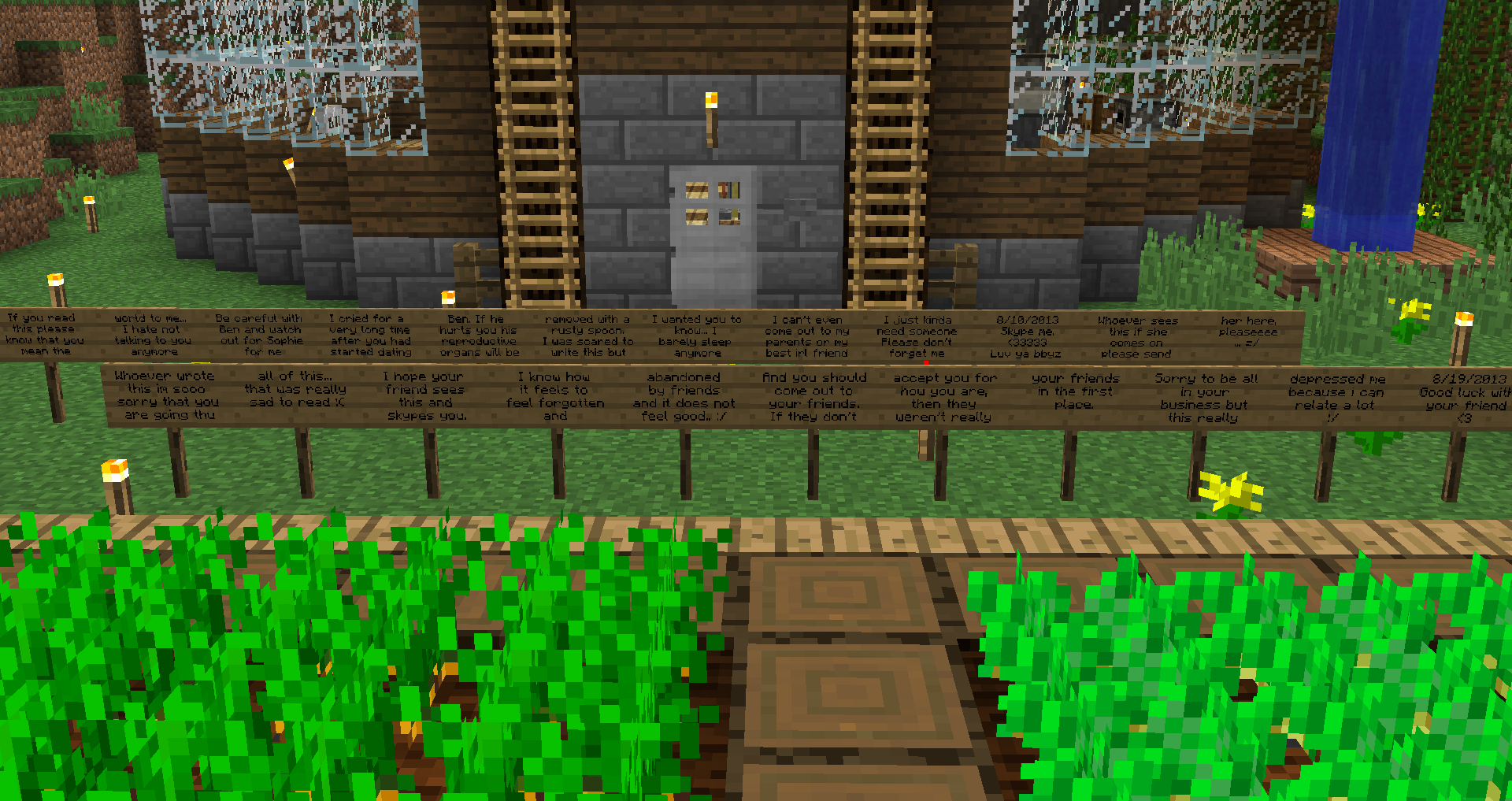

Minecraft player Matt B., whose Reddit username is “worldseed,” is data-mining old servers in search of players’ darkest secrets. (He spoke to us anonymously, saying that he preferred to keep his online and offline identities separate.) Matt wrote two programs in Java: BookReader.jar and SignReader.jar. These applications scan a Minecraft map for every book and sign left behind by players. They then dump all these messages into a text file that Matt can search for terms like “treasure.” Each log entry contains the exact in-game coordinates of the written document.

A few days ago, he founded the MinecraftDataMining subreddit and, so far, has enlisted around 30 volunteers in his efforts to dig up love letters, diaries, and bad high school poetry.

“A lot of the material is just cute little slice of life things,” Matt told Motherboard over Discord. “But it can be kind of depressing.”

Minecraft players can write anything they want on in-game books and signs. As expected, many of these notes are related to things players do in the game. There are recipes for healing potions and written notices that one player has intruded upon another player’s property. But occasionally Matt stumbles across something remarkable.

Discoveries range from the utterly bizarre, like the diary written from the perspective of a chicken found buried underground, to discarded documents of loneliness and grief. In one instance, Matt found what appears to be a player’s suicidal thoughts in a cave hidden below a house on a server that has been closed for five years.

“If I kill myself tonight: the stars will still disappear,” one of the signs read. “The sun will still come up, the Earth would still rotate, the seasons would change…”

Another data mined sign led to what appears to be a memorial of a friend of a player who passed away. Matt was able to use the information from the monument to locate the person’s obituary. “RIP Charlie,” the signs read. “Student, Gamer, Friend…No one here knew him, but I will never forget.”

Not all the signs are so somber. One series tells the story of a missed connection. A player has stopped playing the game, only to return to find their online friend now away.

“I don’t think you guys are ever coming back… ~kat 11/10/15,” the sign reads.

“Hey, it’s Zmoney. Yeah. we’ve all stopped playing Minecraft :/,” another sign replies.

Matt’s data-mining efforts were inspired by an unsolved mystery from his days treasure-hunting in Minecraft. Around 2011, a player reportedly hid a treasure chest containing 64 diamonds somewhere on the Aperture Games Minecraft Server. But the chest never turned up, and the lore of unclaimed loot lingered in the back of his mind for the next seven years.

In hopes of finding the missing jewels, Matt wrote the two programs in Java.

When he went to the chest, someone had already raided it. Though half of the diamonds were gone, he had found something more valuable: all the written communication that remained on the server.

Minecraft is enormous, with each game map covering a surface area of four billion square kilometers. Because of the map’s sheer size, the majority of these correspondences might never have come to light otherwise. Matt said the excavation of a server can net anywhere from 20,000 to 450,000 written documents in the form of books and signs.

To pinpoint unconventional signage, Matt uses keyword searches for provocative terms such as “If you are reading this,” “Hate myself,” and “RIP.” If something catches his eye, he opens the server map and has a look around.

“I don’t mean to gawk or anything,” said Matt. “But if I hadn’t found this stuff, nobody would’ve ever seen it again.”

Elon Musk shows off Falcon Heavy’s Roadster-loving artificial astronaut

Elon Musk is in Florida getting ready for the launch of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket, the first-ever flight of the big new space freight beast. He’s making some final inspections of the cargo, it seems, including a new addition to the cherry red Tesla Roadster that’s going to be on board in the cargo area atop the rocket.

Said new addition is a dummy wearing one of SpaceX’s swanky new astronaut uniforms. Musk’s so-called “Starman” evokes the David Bowie tune that’s going to be playing on the Roadster when it’s launched, hopefully all the way up to space, during Falcon Heavy’s initial test mission on Tuesday at 1:30 PM ET.

SpaceX’s cargo for this one is easily among the most fun things ever put into space, and it’s both symbolic of how this helps Musk achieve his larger mission of reducing human ecological footprint on earth, while simultaneously making sure we can spread our wings and become a truly interplanetary species when the time comes, too.

We’re actually also in Cape Canaveral to witness and report on the historic launch, so stay tuned this week for updates as we near the momentous first journey of this gigantic orbital rocket.

Elon Musk shows off Falcon Heavy’s Roadster-loving artificial astronaut

The tiny, 4K Mavic Air crushes other DJI drones

Every consumer product goes through three stages of life. It’s invented; it’s improved and adjusted; and, finally, it becomes a commodity. There’s not a lot of innovation anymore in microwave ovens, ceiling fans, or toilets — they’ve pretty much stopped morphing. They’ve reached the third stage, their ultimate incarnations.

Drones, love ‘em or hate ‘em, are still in the second stage: They’re rapidly changing direction, gaining features, finding out what they want to be. It’s an exciting period in this category’s life, because new models come out fast, each better and more interesting than the last.

For proof, just look at the Chinese company DJI, the 800-pound gorilla of drones. It releases a new drone or two every single year.

They’ve just introduced a drone called the Mavic Air ($800). It’s so small and smart, it makes you wonder why anyone would buy the 2016 Mavic Pro, which costs $200 more — but it’s not what you’d call perfect.

Meet the Air

The 15-ounce Mavic Air is small — and that’s huge. It folds up for travel: its four arms collapse against the body to make the whole thing small enough to fit into a coat pocket, about 6.5 inches by 3.5 inches by 2 inches. (The top two arms swing horizontally, as you’d expect. The bottom two, though, are hinged in two dimensions: They fold downward and inward, and you have to remember to do those before you do the upper arms. You’ll figure it out.)

Of course, there are plenty of small drones — but not in this league. The Mavic Air, for example, can capture gorgeous 4K video. And its camera is on a three-axis gimbal for stabilization; the video looks like it was shot from a tripod even when the drone was being buffeted by 20 mph winds, as you can see in the video above.

The box includes the drone, a remote control (it uses your smartphone as its screen), a battery, a charger, a set of propeller guards for indoor flying, and a spare set of propellers (in crashes, they’re the first to go).

The Mavic Air is also smarter than any sub-$1,000 drone DJI has ever made. It has depth-sensing cameras on three sides — forward, down, and backward (that’s new) — so that it can avoid collisions automatically in those directions.

Like most drones, this one has an automatic Return to Home feature that kicks in whenever the battery is getting low or if it loses the signal with the remote control. (You can also call it home with one button press whenever you’re just feeling anxious.) Thanks to the cameras underneath, this thing lands exactly where it took off — within a few inches.

The competitive landscape

The Mavic Air’s primary competition comes from two other DJI drones. Here’s the rundown:

- Mavic Pro (2016 model, $1,000). Twice the size of the Air. Folding arms. 4K video. “27 minutes” of flight per charge (in the real world, 22 minutes). Front and bottom collision avoidance. Remote control included with built-in screen (no phone necessary). Very few palm control gestures (see below).

- Mavic Air (2018 model, $800 — the new one). Folds up. 4K video. “21 minutes” per charge (more like 18). Front, bottom, and back collision avoidance. Remote control folds up tiny — even the joysticks unscrew and store inside the body, for even smaller packing. Has the most palm gestures of the three drones — and the most reliable palm gestures. 8 GB of internal storage for video and stills, so you can still record if you don’t have a micro SD card on you. Another $200 buys you a “Fly More” kit that includes two extra batteries, an ingenious folding four-battery charger, and even more spare props.

- Spark (2017 model, $400). The smallest body of all, but its arms don’t fold, so it winds up being bigger for travel. 1080p video. “18 minutes” per charge (more like 11). Front and bottom collision avoidance. Remote control is an extra purchase ($120); uses your phone as a screen. Responds to hand gestures, but not reliably.

True, the Mavic Pro gets a little more flight per battery. And there’s an even more expensive model, the $1,100 Mavic Pro Platinum, that gets “30” minutes per charge.

(Do those seem like incredibly short flights? Yup. But that’s drones for you. As it is, a modern drone is basically a flying frame designed to haul its own battery around.)

But in my book, the Air’s tiny size is far more important than the marginally greater battery life. As the old saying doesn’t go, “The best drone is the drone you have with you.”

In-flight entertainment

You can fly the Mavic Air in three ways.

First, you can use the included remote control. If you insert your smartphone into its grippers and connect the little cord, you get a number of perks — like actual joysticks, which make the drone much easier to fly than using the phone alone. The remote also has a dial at the outer corner for adjusting the camera’s tilt in flight, as well as a switch for Sport mode, which unlocks the drone’s top speed of 42 mph (by turning off the obstacle-avoidance features).

The remote also gives the drone a much greater range. It uses a Wi-Fi connection to the drone, instead of the proprietary radio connection of the Mavic Pro. DJI says that still gives you 2.4 miles of range, but I say baloney; even in the middle of the Texas desert, you’ll be lucky to get half that distance. It doesn’t really matter, though, since Federal Aviation Administration rules say you can’t fly a drone out of sight. (Speaking of the FAA: You don’t need a license to fly the Mavic Air as a hobby, but you do need to register the drone itself. And if you intend to fly it professionally — this means you, wedding videographers, filmmakers, construction firms, realtors, police, and farmers — you have to get permission from the FAA.)

The second way to fly the drone is using your smartphone. It works, but you get a much shorter range (about 250 feet), and it’s harder; DJI’s app has become one super-crowded, complex piece of software.

The third way: using hand gestures. The drone must be facing you at all times, and it has to remain pretty close to you, so this trick is primarily useful for positioning it for “dronies” (selfies from the air). Keep in mind that you also need the phone app with you, though, to turn on the palm-control mode.

You stand with your arm out, palm forward, in a “Stop! In the name of love!” pose. Now, you can “drag” your hand up, down, or around you; the drone follows as though connected to your palm by a magnet. It’s the next best thing to The Force.

New, two-handed gestures let you push the drone farther away or pull it closer to you. And you can now make the drone land by pointing your palm toward the ground and waiting.

In the previous model, the Spark, those palm gestures were super iffy; sometimes they worked, sometimes not. The Mavic Air makes them far more reliable, although I never got the new “take off from the ground” gesture working.

As in other DJI drones, the Mavic Air can follow you as you ski, bike, drive, or run (it tracks you optically — you don’t have to have the remote control on you). Unlike earlier ones, this one doesn’t just hover when it encounters an obstacle; it actually attempts to fly around the obstacle and keep going.

How’s it look?

“4K” may be a buzzword, but it doesn’t automatically mean “great picture”; it could refer to 4,000 pixels’ worth of ugly blotch.

The Mavic Air contains the same tiny camera sensor as the Spark and the Mavic Pro. The footage and stills generally look terrific — anything shot from the air is automatically kind of stunning, and the Air uses more data (100 Mbps) to record data than the Pro does.

Unfortunately, this sensor is still fairly disastrous when it comes to dynamic range. That is, it tends to “blow out” bright areas and “muddy up” dark areas. Alas, those are things you get a lot of when you’re shooting from the sky.

The Air can also do half-speed slow motion (in 1080p, not 4K), and take high-dynamic range photos (not videos).

All of these drones offer preprogrammed flight patterns, called QuickShots, that make great 10-second videos, incorporating flight maneuvers and camera operations that would be incredibly difficult to do yourself.

For example, the one called Circle makes the drone fly around you, keeping the camera pointed toward you the whole time; Helix makes the drone spiral out and away from you; and so on. There are two new ones: Boomerang flies a grand oval around you, up/out and back. Asteroid combines a flight up and away, with a spherical panorama. On playback, the video is reversed, so that it seems to start with a whole planet earth viewed from space, as the camera rushes down toward you. Here, have a look.

But it’s small

Like all drones in this price range, the Mavic Air is complicated and sometimes frustrating. It does a lot of beeping at you, it’s still full of options that are “not available now” for one reason or another, and it still doesn’t come with a printed instruction manual.

And yeah, someday, we’ll look back and laugh at an $800 drone that flies for only 18 minutes.

But you can’t buy a dream drone that doesn’t exist. And among the ones that do, the Mavic Air is ingeniously designed, impressively rugged, and incredibly small. Its features beat the cheaper DJI Spark in every category — and even the more expensive Mavic Pro in almost every category.

In other words, if you’re the kind of person considering a drone, the Mavic Air strikes a new sweet spot on the great spectrum of drones, somewhere between beginner and pro, between tiny and luggage-sized, between cheap and pricey. Invest as much time learning it as you’ve invested in buying it, and you’ll be flying high.

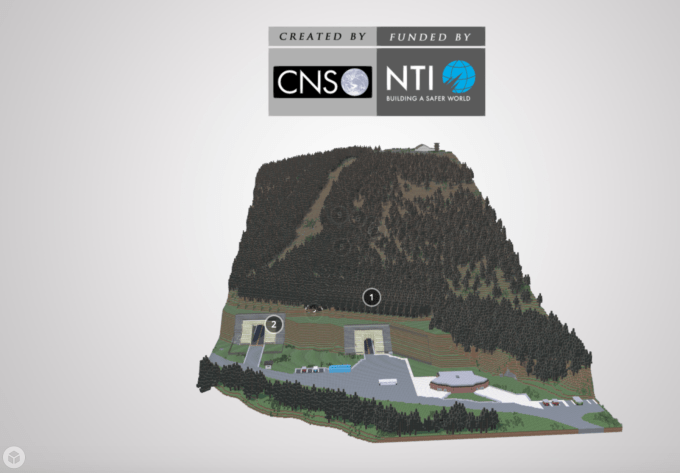

Casually prep for nuclear war with this Minecraft tour of the Russian and American fallout bunkers

Virtual tourism is a little heavy in 2018. Sure, you’ve seen the Minecraft Eiffel Tower and beamed aboard the Minecraft USS Enterprise, but have you considered where you might wait out the end of days? Well, not you exactly, but people more important than you.

To draw attention to the escalating threat of global nuclear annihilation, the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), which works to “prevent catastrophic attacks with weapons of mass destruction and disruption—nuclear, biological, radiological, chemical and cyber,” has partnered with the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies to craft a virtual tour of the nuclear fallout facilities that Russian and/or American leadership will be whisked into in the event of nuclear war.

The team has really outdone itself with the Fallout-esque teaser video.

As NTI explains:

Nothing better illustrates the continuing absurdity of plans to fight a nuclear war than the massive complex of underground bunkers that the United States and Russia have built to survive and fight on even after both societies have collapsed. To help explain the scale of these facilities, we have reconstructed two, Site R in rural Pennsylvania (also known as Raven Rock) and the Kosvinsky underground command facility in Russia, roughly to scale using the popular immersive gaming platform Minecraft.

For anyone with the game, you can fire up a multiplayer instance of Minecraft, select “direct connect” and put in server address 185.38.151.31:25566 to visit Raven Rock, the underground makeshift Pentagon located near Camp David, or 185.38.151.2:25566 to tool around Kosvinsky, “a survivable command post” that serves as Russia’s equivalent. NTI cautions that it only lets zombies out on the weekends.

For anyone without Minecraft, you can take an in-browser virtual tour on NTI’s post about the project, which is also chock full of interesting nuclear bunker facts that put the existence of such underground facilities in an appropriately dark context. The tour is much clunkier outside the game, but the Minecraft experience actually looks pretty cool in that eerie we-definitely-won’t-survive-but-these-people-probably-will way.

Casually prep for nuclear war with this Minecraft tour of the Russian and American fallout bunkers

Minecraft had 74 million active players in December, a new record for the game

We’ve all been very impressed by the numbers that PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds and Fortnite have been putting up in the past few months. PUBG is regularly pulling in three million concurrent players and more than 25 million people own it on Steam, while Epic’s action game has 40 million players, and recently passed the 2 million concurrent player barrier. But there’s a game that’s outstripping them both: Minecraft.

New head of Minecraft Helen Chiang has revealed that the game had 74 million active users in December—the most in a month since it released nearly nine years ago. In total, more than 144 million copies of the game have been sold. “We just recently set a new record in December for monthly active users, so now we’re at 74 million monthly active users—and that’s really a testament to people coming back to the game, whether it’s through the game updates or bringing in new players from across the world,” she told PopSugar.

Now, we don’t know how many of those are on PC. Minecraft is on every major console, as well as on tablets and phones, so it’s not a fair fight. But still, 74 million active players is a hell of a lot. Combining PUBG’s PC and Xbox One sales figures gets you to about 30 million. And that’s total owners, not active players (granted, Minecraft has been out for many years longer, and at the current rate PUBG is going to get there eventually).

I’ve heard a lot of people frustrated with the lack of meaningful updates to the game recently, which is a fair criticism. 2018 does look like a fairly big year for it, though, starting with a beefy ocean update coming in Spring.

What would you like to see change in Minecraft?

Minecraft had 74 million active players in December, a new record for the game

Mojang will talk about 2018 Minecraft updates at the PC Gamer Weekender

Minecraft developer Mojang will join us on-stage at the PC Gamer Weekender to discuss future updates for the game, as well as offering insight into how features for the game are conceived and developed. The studio’s lead creative designer Jens Bergensten will present at 16.00 on Sunday, 18 February at the Olympia in London. Come along, and learn more about what they’ve got in store for 2018.

Minecraft, of course, just had its biggest active month ever with 74 million users. Hell, you know what it is. This is a great opportunity to go behind-the-scenes with the developer, and while you’re at the Weekender, you can check out many more speakers, games and booths. Tickets are available now from £12.99, and you can save an extra 20% with the voucher code PC-GAMER20.

Mojang will talk about 2018 Minecraft updates at the PC Gamer Weekender

Minecraft Developer’s Scrolls Will Finally Shut Down Next Week

Minecraft developer Mojang announced that its tactical card game Scrolls would be shutting down on Tuesday, February 13.

Released at the end of 2014, Mojang revealed they would stop development of the game way back in June of 2015. They committed to keeping the servers running until at least July of 2016, though they’ve clearly lasted much longer than that.

As part of the announcement, Mojang also revealed that they are working to make the Scrolls server software public, allowing the community to host their own servers and continue playing online. They said they can’t guarantee this will happen, but that they have “high hopes that we’ll be able to do this in the next few weeks or months.”

As a final goodbye, a community tournament will be held on February 11. Additionally, Mojang developers will be online playing Scrolls with its players on February 9.

Minecraft Developer’s Scrolls Will Finally Shut Down Next Week

King High School teacher prepares students for the future with ‘Minecraft’

As technology offers students more access to the digital world, teachers have to start thinking outside the box on how to prepare their students for the future.

King High School teacher Katherine Hewett is doing just that, but using an unorthodox but futuristic method.

“I use the game Minecraft to teach my students about 21st century skills,” she said.

That’s right, Hewett is using video games in the classroom, and it’s not as crazy as some may think.

“About five years ago, I was having conversations with my students about video games,” said Hewett, who is a career and technical education teacher at King. “I was listening to them tell me about how video games impacted their learning and as a teacher, this was an awakening. I realized kids were receiving an alternate education when they got home.”

Hewett said she started to ask herself questions about who was teaching and mentoring these students when they entered these virtual worlds.

“I was wondering why weren’t adults, teachers, not taking more of an interest and using this is as a tool?” She said.” Why weren’t they in those worlds with them?”

That was when Hewett decided she was going to integrate to virtual reality.

Her goal? To teach the students design, coding, programming and visual media so that they are prepared for the future.

And Minecraft came on to the market, Hewett knew she had a chance to make this dream a reality.

“Here was a VR space that visually looks like Legos and had sandbox features to build, create and design 3-D worlds,” she said. “I approached the administration about it and when I suggested it to them, they were all in! I remember, when we ordered the licenses they told us we were 1 in 700 in the country that integrated the game into a class.”

Since Hewett started the course in 2013, she has had students find careers in the information technology field working for big data companies or working on virtual reality projects of their own.

Hewett said the class starts with a theme topic.

“Each class agrees on a topic where they then start researching and begin replicating the build in Minecraft,” she said. “Students collaborate and communicate to create a really large size 3-D model.”

This year’s classes have different worlds as the game is integrated into all of Hewett’s classes. Some class periods are designing fantasy worlds like Mario World and Tron whereas others are replicating real life places like Alcatraz Prison and the Winchester Mansion.

Sophomore Brendan Fuller said taking the animated course will open doors for him in the future.

“I’ve always been great with technology, but taking this course has definitely taught me a thing or two about animation,” Fuller said. “I want to use these skills one day when I become an architectural engineer. Learning how to create 3-D models now will benefit me greatly.”

Hewett said “Minecraft” has not just changed her students lives but hers as well.

The King High School teacher said as she was working on her doctorate, she focused her dissertation on her class. Now, her research on the “21st Century Classroom Gamer” has been accepted into the international journal “Games and Culture.”

“This course is everything,” she said. “I’ve learned so much with my students immersing myself into this gaming culture.”

Hewett said the animation course is a first step. She plans to take the next step with virtual reality soon.

“We don’t know what the jobs will be in the next five to 10 years,” she said. “So I’m trying to teach them all the 21st century skills they need to prepare them for jobs that don’t even exist yet.”

King High School teacher prepares students for the future with ‘Minecraft’

Dragon Quest Builders Nintendo Switch REVIEW: Minecraft meets Zelda RPG is no bad thing

Some years later and with the launch of Nintendo’s Switch, what better platform to port this RPG-Builder to and explore it for the first time. Especially as Dragon Quest is one JRPG that holds a bright candle in our hearts.

Set after the events of the original Dragon Quest, Builders takes us through an alternate timeline in the long since destroyed Alefgard in which the few left no longer have the ability to build or create.

A simple enough premise giving you enough of a jumping off point to begin your immersion into the world but one which requires essentially no prior knowledge of the previous entries to understand or even fall in love with the games style, enemies and overall shot of nostalgia with its classic Zelda feels.

After a fairly thorough tutorial, giving you all the know how you need to get building, from full on structures to surviving in the harsh wilderness of Alefgard (hot tip, don’t stray too far from a light source when the night falls) Dragon Quest Builders takes the training wheels off and leaves you to build as you see fit.

Dragon Quest Builders Screenshots

It’s a hugely satisfying experience, especially when your creations can be built, upgraded and even taken down again with simple commands that feel natural to control.

There are story-based mission of course, as towns folk will need a hand from time to time building anything from simple bedrooms to bathhouses and even wandering the more dangerous parts of the world in search of precious materials and possible new towns-folk.

Simplicity is at the games core though as combat is just as easy to adopt as the main building mechanic, opting for a classic Zelda-esque real-time combat system which is much pacier than the series turn based combat and fits extremely well with the over feel of this iteration.

And while the world here may seem a little different for experienced Dragon Quest fans there are plenty of familiar monsters to deal with; from metal-slime to golems, which appear the further, you delve into the wilderness. Each dropping crucial building materials.

Exploring while treacherous is seldom a waste of time, as all areas of the world from it’s deserts to it’s forests have plenty of secrets to distract you and give you yet another reason to stray from your quest and sink some more time into.

As an array of the games nasty’s tear towards all four walls of your towns, you’ll need to prepare barriers and automated defences to survive the onslaught.

These miniaturised tower defence moments are fun and challenging without entering into hair pulling territory.

When you factor in the games free build mode, allowing you to simply create to your hearts content minus the enemy onslaughts and limited supplies, then it shows how

Dragon Quest Builders is a big game disguised in a simple package, and one that fits perfectly with the Switch.

We found ourselves constantly dipping in and out on train journeys before docking at home for longer sessions, delightfully hooked on the games world and that niggling need to spend 5 more minutes building the next addition to our towns.

Whether you’re new to Dragon Quest or this style of creation based game, you’re sure to be fully enthralled.

THE VERDICT – 4/5

THE GOOD

• Simple but addictive building system

• Great soundtrack

• Familiar Monsters

• Nostalgic feel and aesthetic

THE BAD

• No multiplayer

Dragon Quest Builders Nintendo Switch REVIEW: Minecraft meets Zelda RPG is no bad thing

Minecraft enthusiasts, novices unite

Though Philadelphia resident Gabe Young doesn’t have enough hours in the day to explain all of the twists and turns players of the video game Minecraft can take, this weekend he and a team of gaming enthusiasts will attempt to share what makes the game truly unique with Peninsula residents.

With opportunities to experience the game in virtual reality, live entertainment on four stages and several young gamers sharing tips and tricks with fans of the game, Minefaire, the event Young is coordinating at the San Mateo County Event Center this Saturday and Sunday, is set to immerse players of all ages and ability levels in a game that’s captivated the minds of many.

By gathering resources and building structures like staircases, mazes and amusement parks in the game, Minecraft players can create their own worlds and solve problems in creative ways, said Young. In giving players the option to work with or compete against others and code within the game to create maps of new worlds, Minecraft offers players a seemingly boundless environment to explore, said Young.

“Basically there’s no limit to what you can do with Minecraft,” he said. “Your only limitation is your imagination.”

And perhaps that’s why so many kids have been drawn to the game since it was released in 2011, drawing anywhere between 10,000 to 15,000 people to the five Minefaires Young and event cofounder Chad Collins have pulled off since they started convening enthusiasts in 2016.

Young said he enjoys seeing players, many of whom are accustomed to playing on their own, come alive when they meet others as bullish on the game as they are. Though the events are aimed at attracting all ages, Young said kids ages 6 to 12 have come to enjoy meeting peers and discovering new ways to approach the game. Getting the chance to meet other youth who have made a name for themselves on YouTube as experts in the game is as exciting as it’s been for generations of kids to meet star athletes and celebrities, said Young.

“These kids they see these YouTubers as their A listers in a way that we can’t imagine,” he said. “It gives a lot of these kids the motivation and the energy to keep going.”

Though Young and Collins have experience convening kids at events like a Lego convention, Young said it wasn’t until they saw their own children playing the game that they saw how captivating it was and decided to focus their energy in planning Minecraft events.

“We were blown away with how much we’re learning by watching [them] learn,” he said. “There’s a lot of things happening in these little brains.”

A go-to activity for his four kids before dinner, Young said he’s realized how much the game is teaching them about topics like agriculture, history, geology and architecture, all without their feeling like they are being taught. And he’s hoping the same understanding spreads among parents in the 11 cities expected to play host to Minefaire this year.

Young’s advice to other parents attending the event with their kids is to be open to experiences they might not have had as kids and let them teach them about a game they’ve spent hours exploring.

“These kids are going to grab their parents by the hand and say look what I’m doing,” he said. “Now they’re going to have a better idea of how to guide their kids.”

Minefaire will be held 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Feb. 10 and 11 at the San Mateo County Event Center, 1346 Saratoga Drive. Visit minefaire.com for more information and to purchase tickets, which start at $45 and are free for children age 2 and under.

Get Nintendo, Overwatch, and Minecraft 2018 Gaming Calendars for Only $4

Yes, we’re a week into February now and we have smartphones and whatnot in 2018, but awesome gaming calendars for only $3.74 each? You could literally mark your Nintendo calendar with all of the awesome Switch releases coming up this year. You can check out the full list of discounted calendars along with their official descriptions below.

The Legend of Zelda 2018 Wall Calendar – $3.74: Set off on an epic journey with our hero Link as he embarks on a series of quests to save the Hyrule Kingdom and Princess Zelda. The Legend of Zelda 2018 Calendar takes you into the action-packed adventure with colorful, iconic images from one of the bestselling Nintendo video games.

On a related note, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild The Complete Official Guide Expanded Edition is on sale for 40% with a release date of February 13th.

Super Mario 2018 Wall Calendar – $3.74: Join Mario on an incredible adventure as he navigates the world of the Mushroom Kingdom in this 16-month wall calendar. Featuring fan favorites including Luigi, Bowser, Toad, Princess Peach, and Yoshi, this calendar is sure to make 2018 a year of fun and games.

Splatoon 2018 Wall Calendar – $3.74: Make your way through 2018 with colorful 3D art from the chaotic world of Splatoon, the newest video game franchise from Nintendo. Splatter enemies and claim your turf with ink-spewing, squid-like characters called Inklings. Change from humanoid to squid and back again to make your way across the battlefield at top speed.

Overwatch 2018 Wall Calendar – $3.74: Overwatch, Blizzards highly anticipated multiplayer game, is an action-packed adventure set in the not-so-distant future, after a fierce battle between humans and robots. Named for the peace-keeping task force dedicated to protecting humanity, Overwatch offers a full range of playable characters including both females and males, robots, and even a gorilla. Keep track of important dates, birthdays, anniversaries and more with this Overwatch wall calendar.

Minecraft 2018 Wall Calendar – $3.74: Build, explore, survive, and thrive in Minecraft, the game in which a few blocks are the beginning of many an adventure. Create a castle, fight a battle, search for resources, and encounter friendly and hostile mobs in the 2018 Minecraft Calendar that includes the last four months of 2017. The spacious grids, printed on paper certified by the Forest Stewardship Council, include plenty of room to write in your appointments and plans for Minecraft world domination.

Note: If you purchase one of the awesome products featured above, we may earn a small commission from the retailer. Thank you for your support.

Get Nintendo, Overwatch, and Minecraft 2018 Gaming Calendars for Only $4

Constructing Religious Worlds With Minecraft

Jeremy Smith wanted to talk about Jesus, so he picked up a shovel and headed out to build a tunnel.

A virtual shovel, that is. As both a Christian and a fan of the video game Minecraft, Smith has one foot in two different communities coming into contact more frequently in the fuzzy halls of cyberspace.

And, as a senior writer at the online ministry ChurchMag, Smith uses each of these communities to serve the other. He “vlogs” — creates online videos of himself playing Minecraft — while simultaneously explaining Christian ideology in a series titled “Minecraft Theology.”

“I wanted to look at some of the more basic stuff, some of the core competencies of Christianity,” he said in one of these videos as his Minecraft icon sped across a screen full of the chunky landscape Minecraft allows users to create and navigate via a computer mouse.

“Part of the prayer process is admitting that you’ve sinned. If you are of the mindset that you are perfect, then you should probably just go ahead and turn this episode off because I got nothing for you,” he continued. “We have confession when we say ‘yes’ to Jesus and become saved.”

In the realm of video games, the 149 views Smith’s video has logged may be far from viral, but Minecraft is becoming what some video game makers hoped Christian-themed games like Catechumen and Adam’s Venture that failed to sell well would become — a tool for exploring and advancing religion among gamers.

“Because Minecraft is so open any player can design a world,” said Vincent Gonzalez, a scholar who did his doctoral dissertation on Christian video games. “And whenever things are open, religious people tend to use it to express themselves.”

Ithaca College professor Rachel Wagner sees the use of video games like Minecraft as part of what she calls the “gamification” not only of religion, but of the world. She says religions and video games have several things in common — rules, rituals, and a bend toward order and structure.

“Even if they are ‘open’ in the sense of allowing players to construct entire worlds for themselves, as Minecraft does, games always offer spaces in which things make sense, where players have purpose and control,” she said. “For players who may feel that the real world is spinning out of control, games can offer a comforting sense of predictability. They can replace God for some in their ability to promise an ordered world.”

Minecraft is what techie types call a “sandbox” game: It has few rules, so players can dig in anywhere and build what they like. They build with virtual bricks — think digitized Legos — to create bulky buildings, plants, people, anything, in mostly primary colors.

There are Minecraft versions where players try to survive or go on adventures of their own devising. And there are versions where people — sometimes children, sometimes adults like Smith — construct homes, buildings, bridges, churches and other houses of worship.

Some Minecraft users even “build” their own religious icons. Using blocky “skins” — Minecraft lingo for a character — they create Jesuses, popes, priests, rabbis, angels, and more to populate Minecraft worlds everywhere.

But while Minecraft can be used by players of every religion, it seems to be most popular among Christians. Gonzalez, who catalogs religious video games at religiousgames.org, estimates there are about 1,500 religion-themed video games, of which two-thirds are Christian.

Take a peek at Planet Minecraft, a fan site where users can share their creations. It lists 716 “Jesuses” and about 1,000 Catholic priests, but only 58 Jewish rabbis. There is even a Minecraft Richard Dawkins for virtual atheists.

Certainly, not all Minecraft players use religious skins or the churches and other houses of worship they build for some spiritual purpose or for proselytizing. But how they use them is hard to pin down.

“No one’s pastor is telling them the best way to minister to people is to pretend to be Jesus in a Minecraft world,” Gonzalez said. “So the question of why people want to dress up as Jesus and go around in Minecraft is hard to say.”

Still, Minecraft and other computer and video games have become so closely aligned with religion in some circles that the American Academy of Religion created a scholars’ group dedicated to its study four years ago.

“For most people, their virtual lives are an extension of their real lives,” said Gregory Grieve, a professor of religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro who has studied the two decades religious people have engaged in video games. “Among Christians it was a place for proselytizing and a place for meeting people they would not otherwise meet. People who are religious just see these games as an extension of their religious practice.”

Some build houses of worship — YouTube is rife with virtual tours of churches, cathedrals, synagogues, and mosques, both real and imaginary. Some build Noah’s Ark or Solomon’s Temple or their own versions of Jerusalem and other “Bible lands.”

The Australian digital design firm Islam Imagined encourages young users to build the “mosque of the future,” and Jewish educators are enlisting Minecraft to visualize Jewish history and culture for students.

Others users create faith-based Minecraft “servers” — private virtual enclaves where members agree to certain rules (no swearing is a common one) and play the game in a form of religious fellowship.

These groups recently became a meme — or joke spread rapidly among internet users — in which users sardonically responded to foul language by uttering different versions of: “Sorry sir, this is a Christian server. No swearing allowed!”

But Eric Dye, editor of ChurchMag, says its Christian-oriented Minecraft server is merely a reflection of how its users see, or want to see, the real world.

“We can build things in it, like themed cities, and there is actually a church,” he said. “It is not like we have church services or anything but it seemed something fun to have. It seemed fitting. That is why you see religion manifested in Minecraft — it is just an extension of people’s interests in what they create.”

Dragon Quest Builders for Switch review: Minecraft for less imaginative people

Chad Sapieha and his little reviewer-in-training came away with slightly different takes on Square Enix’s blocky crafting RPG

These are all features I’ve long wished for in Minecraft. And seeing them implemented within the familiar world of Dragon Quest – a long-running series of Japanese role-playing games that I’ve played for decades – was a joy for me when I played the game on PlayStation 4. But it seemed like I wasn’t in the majority. The game had sold a little over a million copies worldwide, last I heard. That’s not terrible, but it’s just a tiny fraction of the more than 130 million copies of Minecraft that have been purchased by kids around the world.

Still, I thought maybe people just hadn’t given it a chance. So I let my 12-year-old kid – a long-time Minecraft devotee and lover of role-playing games – loose with the soon-to-be-released Nintendo Switch edition of Dragon Quest Builders thinking it was bound to become her new obsession. Turns out she’d rather be free to follow her imagination than locked into linear story and told what to do.

Here’s a transcript of the discussion we had after she’d been playing for a few days. It will serve as our review.

Me: I thought you’d have a great time with Dragon Quest Builders. It basically combines the mining, crafting, and building parts of Minecraft with a colourful Japanese RPG – one of your favourite kinds of games. What did you think of it?

Me: I thought you’d have a great time with Dragon Quest Builders. It basically combines the mining, crafting, and building parts of Minecraft with a colourful Japanese RPG – one of your favourite kinds of games. What did you think of it?

Kid: Honestly, it isn’t my favourite. For a few reasons. At the start the problem was mostly controls. I just didn’t like how they were set up. That’s something I can eventually grow used to, but I also didn’t like how you couldn’t explore the whole world right from the start. The story kind of limits you to a specific area – an island – because of some “unseen force.” There are also some things about the inventory that I didn’t like. I had to go back to my chest to store stuff all the time. It’s definitely not an awful game, but it’s not my new favourite.

Interesting. The control problem you mentioned happens to me all the time. Having played games for decades, I expect certain types of games to have specific button schemes. When a developer tries something new – like, say, uses the top action button to jump rather than the bottom one – it can be frustrating. At least until I get used to them.

I’ve kind of grown used to the controls now, but I still get frustrated. This game uses the A-button to get to the menu, which makes no sense to me because it’s your primary button. I’m always pressing it thinking it should do something else. Or at least I was at the start. It’s gotten a little better.

Fair enough. Personally, I have to say that I like Dragon Quest Builders a bit more than Minecraft, mostly just because it has a story and objectives. Minecraft is great when it comes to creative freedom, but I can only build towers and castles for so long until I get kind of bored. It might just be a lack of imagination on my part, but I like to have missions and objectives. Dragon Quest Builders gives us that.

Fair enough. Personally, I have to say that I like Dragon Quest Builders a bit more than Minecraft, mostly just because it has a story and objectives. Minecraft is great when it comes to creative freedom, but I can only build towers and castles for so long until I get kind of bored. It might just be a lack of imagination on my part, but I like to have missions and objectives. Dragon Quest Builders gives us that.

Well, I’d like it more if I could at least leave the island and do whatever I wanted to do. That way I’d have the choice. I could either do the story stuff, or I could go off and just do whatever I wanted to. Find more resources to build stuff. I guess I kind of get why they can’t let you do that – it’d be hard for the designers to tell a story that makes sense if you could go places you weren’t supposed to see until later on – but it’s what I want. Minecraft might not have a story, but I can do whatever I want, whenever I want. I think that’s more important to me.

I get you. And I’m the first to admit that the story in Dragon Quest Builders isn’t anything special. Standard fantasy stuff involving monsters and world saving. But it provides a reason and context for everything you do, which I like. I also like how we get blueprints for building certain buildings and objects. They provide a starting place and a seeding ground for ideas – kind of like a Lego kit with an instruction booklet. Afterward you can go crazy building anything you like, but that initial guidance is nice.

Yeah I really liked the blueprints, too. I thought it was a cool spin. Even in the Lego games you don’t really get blueprints you can build piece by piece, not even in Lego World where you’re free to build anything. I think that’s one of the best parts of Dragon Quest Builders. Something other people who make games like this might want to copy.

Another thing I liked was how this game handles crafting. Once you have what you need for a complex object, you can just build it, instantly. That’s smart. When it comes to crafting, how and where in the world you choose to place what you’ve made is the fun part, not sorting through your inventory to pick out all the pieces you need.

Another thing I liked was how this game handles crafting. Once you have what you need for a complex object, you can just build it, instantly. That’s smart. When it comes to crafting, how and where in the world you choose to place what you’ve made is the fun part, not sorting through your inventory to pick out all the pieces you need.

Yeah, the designing is definitely the fun part. But, in Minecraft‘s defence, in newer versions you can go into the settings and change it so that you don’t have to manually go through your inventory to make stuff like beds and doors.

How about the look and feel? I’d be lying if I said Minecraft‘s retro pixelated aesthetic hasn’t worn a little thin with me. Dragon Quest Builders keeps the blocky vibe, but adds more vibrancy and detail. It just feels like it has more character.

Yeah. I do like how it looks more than Minecraft. There are little details, like bits of grass on blocks, that make things a bit more realistic. And I like that the characters in this game are like little cartoon characters with more personality. Maybe it’s just because of how much I’ve played Minecraft, but sometimes it gives me a headache. I’ll go to sleep at night and close my eyes and just see its blocky graphics.

Does Dragon Quest Builders make you want to try other Dragon Quest games? Part of the reason for creative spinoffs like this is to get new people interested in the core series. Other Dragon Quests aren’t really like this one – they’re much more traditional JRPGs – but they contain similar elements, like monster types and the style of dialogue.

It makes me interested in them. But I don’t know if I ever would. I love role-playing games, but they take so much time. I think I’ve got too many to play already. And aren’t there, like, a dozen of them? That’s, like, hundreds and hundreds of hours. I could never catch up.

Good point. Final verdict?

Good point. Final verdict?

I think you know I’m pretty generous with ratings, so keep that in mind. I think I’d probably give it like a seven or seven-and-a-half out of ten. The idea is really good, and the animation is cute, and even the story isn’t half bad – and you can kind of skip it if you don’t like it – but something about it just doesn’t really click for me the way it does in some of my favourite games. I’ll probably keep playing when I get tired of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild or if I’m not online and can’t play Splatoon2, but there are other games I’d rather play.

I like to think I’m not quite as generous as you are with scores, but I’d give it a seven-and-a-half or even an eight. I actually think older players will like it more than kids, both because of the name – there are lots of grown-ups out there who grew up with Dragon Quest – and the guided elements. Problem is, it’s clearly targeted at kids, who, like you, might want a little more freedom and fewer limitations. I guess it’s a good little game that’s maybe stuck between audiences.

It’s true old people have no imagination. Every time you play Minecraft you just build big ugly towers into the sky made of random things and then jump off them into the water. Then you stop playing. And when we play Lego you’re just like Will Farrell in The Lego Movie, except you don’t have his hair or teeth. You just stick to the instructions and leave stuff built until it gets dusty. So, yeah, Dragon Quest Builders is probably about your speed.

Dragon Quest Builders for Switch review: Minecraft for less imaginative people

Dragon Quest Builders review – make the switch from Minecraft

One of the best alternatives to Minecraft comes to Nintendo Switch, with a charming spin-off that’s not just for existing fans.