by Stone Marshall | Nov 30, 2014 | Minecraft News |

It was only sometime before Halloween that I’ve tried out Minecraft and like every other person who’s tried out the sandbox game, I was instantly hooked. Before I knew it, my waking moments were interspersed with how to connect that other village to my home, or how to create that next great home. The game’s so open-ended, each playthrough is a new experience and there’s a new story to be created everytime you delve into the world.

There is another version of Minecraft that’s available on smartphones and that’s Minecraft: Pocket Edition. It’s a cool version to have, because basically it’s Minecraft on the go. What’s more is that you really don’t need a Net connection to be able to play the game—it’s that awesome, I know. However, the small screen and the limited options might be a big let-down.

Same Minecraft, Different Features

While it’s essentially the same Minecraft that we all love, there are some options that are left out. For one, while the build-your-own-piece-of-paradise property is still in effect, there are other missing features; the survival elements in the PC and console games such as brewing and hunger are gone, and so are the bosses and the dimensions such as the Nether or the End.

The only time you’re going to need a WiFi or an Internet connection is when you’re going to play with friends. There is an option for a multiplayer in Minecraft: Pocket Edition, and it brings to mobile phones what LAN inter-connectivity does to PC players or to console players.

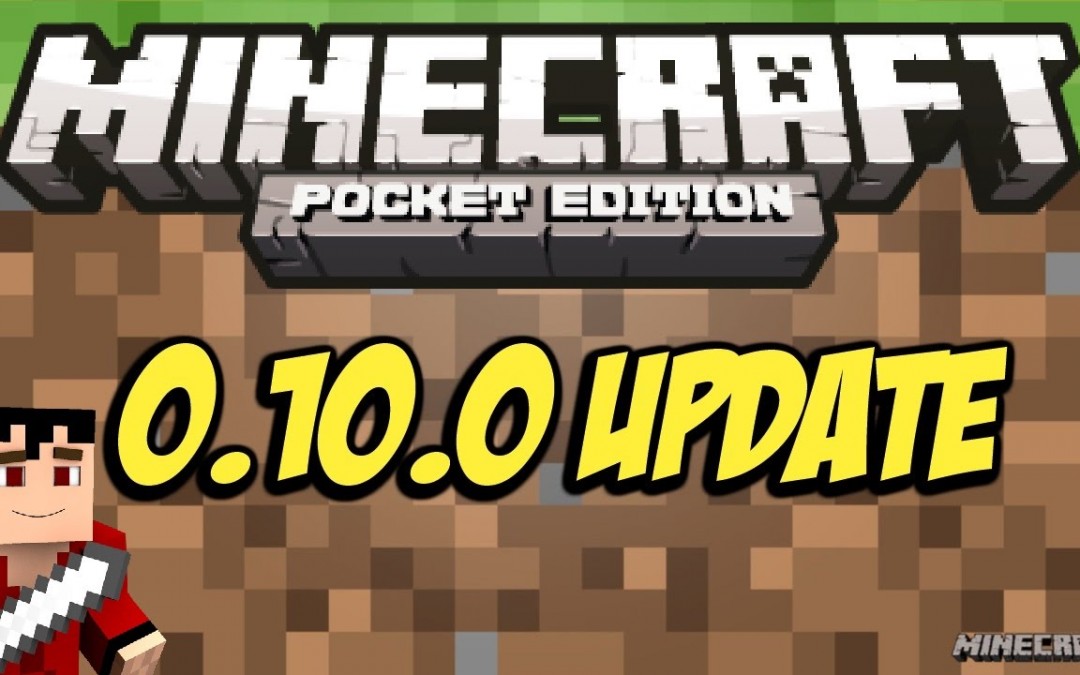

Recently, in a bid to give Pocket Edition players more content, update 0.10.0 was released for Minecraft: Pocket Edition.

New Contents, New Challenges

Update 0.10.0 is to smartphone Minecraft players what 1.8.0—otherwise known as the Bountiful Update—is to players of the PC and the console formats. There are a lot of bug fixes that are resolved with this update, but that’s not all. Here we have a list of the features that this update brings courtesy of Mac Rumors and The Minecraft Pocket Edition Wiki:

- Updated Shaders.

- Gold Ore is more abundant in Mesas—a get-rich-quick scheme?

- Fences and fence gates receive an update.

- Swamp water now looks more like swamp water should.

- Sun is now exponentially bigger.

- Water receives smoother light rendering.

- Day or night doesn’t affect Creative mode.

- Water pushes more things away with force.

- Chest layouts have been changed.

- Brightness can now be toggled.

A Timely Update

In the past, Mac Rumors reveals that Minecraft Pocket Edition was widely reviled due to the fact that they don’t live up to expectations of people who have already played versions available on the PC and the console. However, many updates later, and thanks to ones such as 0.10.0, Minecraft enjoys a bigger similarity with its console and PC cousins.

For those who want to play Minecraft Pocket Edition, it’s available on the Google Play Store and Apple’s App Store.

Read Original Article Here:

by Stone Marshall | Nov 28, 2014 | Minecraft News |

Earlier this week, the creator of indie crossover hit Minecraft revealed an impressive statistic – the game, which started out as the personal project of creator Markus “Notch” Persson, has now sold over 33 million copies worldwide, on PC, Xbox and mobile. This chunky combination of adventure game and Lego construction set has beguiled players for over two years, without a multimillion-dollar development budget, or blanket advertising.

At first the success of the game was puzzling. Its procedurally generated worlds are constructed from hefty blocks, giving the environment and everything in it, a simplistic, retro look. Originally released as an unfinished beta version, players had to wade through software bugs and mechanical uncertainties, using the game’s complex crafting system to build homes and contraptions, but having to share information on what worked where – there was no tutorial.

But actually, that has been a part of Minecraft’s beauty. It is an organic creation, not just because every time you start a new game the whole landscape generates anew, but because it has been developed in tandem with play. Game modes, new monsters, new features, new farm animals – many have come and gone, and then been tweaked and changed and put back in – often in response to user feedback, like one giant science lab. Very basically, there remain two different experiences: the Creative mode which gives you access to all the building blocks and “mobs” (AI characters) in the world allowing you to build anything you want; and the Survival mode, where you must mine for minerals with which to craft items and weapons, while avoiding exploding creepers, giant spiders and lurking zombies. In this mode, players have all day to explore and build, but when night comes, the monsters are abroad and you must return to your self-built house. Safe and warm.

“Minecraft is designed around a really compelling fantasy,” said Chris Goetz, a doctoral candidate in the department of film and media at UC Berkeley, to the LA Times last week. “Play in the real world is often about exploring the unknown world around you and then returning home where you feel safe. Minecraft is a place where kids can work through those same impulses. It’s like kid utopia.”

Advertisement

This is particularly resonant to me, and I suspect many other parents with autistic children. My seven-year-old son, Zac, was confirmed on the scale earlier this year, although in a lot of ways we’ve always known. He has a somewhat limited vocabulary, and finds noisy social situations like schoolyards frightening and confusing; he is demonstrative, but has difficulty with empathy. We have watched as his younger brother, Albie, has overtaken him on things like reading and writing. But he is funny and imaginative and wonderful.

And like a lot of children with an autism spectrum condition, he loves Minecraft. From the moment I downloaded the Xbox 360 edition and handed controllers to him and his brother Albie, they have been addicts. At first, they simply trudged across the rolling landscapes, randomly attacking the sheep, cows and ducks that graze each Minecraft world. They would throw together weird hovels, filled with random doors and windows, huge gaps in the walls, bizarre jutting extensions, like nightmarish sets from a German expressionistic horror movie.

Now, they construct immense palaces and giant inhabitable robots – usually made out of gold and glass. They are the Liberaces of virtual architecture. They explore the game’s growing systems; they avidly download all the regular updates which add new features, new creatures, new narrative possibilities – they devour them all.

It is a beautiful thing to watch, not least because Zac sometimes finds the world as we know it inexplicable. Guiltily, we have often laughed at his constant refrain of “What?!” whenever we talk about or point out something he doesn’t understand. He jokes about it too. “I’m good for nothing!” he wails in mock misery when he mishears or fails to comprehend something the rest of us got instantly. For Zac, Minecraft represents an utterly logical yet creatively fecund world that he can explore and manipulate on his own terms. If people with autism crave order and control, Minecraft provides it, only within an environment that also allows and rewards discovery.

Zac’s experience is, I think, a microcosm of the game’s true appeal: it is utterly malleable. Minecraft is not a game really as much as a tool, a gamified design application – an imaginative conduit that stamps only a fraction of itself onto individual projects. Recently, staff at the Mattituck-Laurel library in Mattituck, New York, built a complete version of their building in the game. It’s not a mere folly, as an article in the School Library Journal points out:

Each room of the Minecraft library offers a clue inside treasure chests tucked into the virtual shelves. Clues provide students with a summary of the plot, title, author, and call letters – so children can locate the books inside the physical library.

Beyond this, Minecraft is now being widely used in education. Geography teachers get children to model real-life buildings or villages; physics teachers use it to teach simple fluid dynamics and mechanical properties. Minecraft developer Mojang works with an organisation named MinecraftEdu, which distributes a special version of the game to schools with extra educational tools. The game has also been picked up by Autism charities, which run dedicated multiplayer servers where autistic children can meet up and create together. AutCraft in the US and APTTA Craft in the UK are two examples.

Meanwhile, the game keeps growing. Updates are regular, and a new “Mash-Up” pack has just been released for the Xbox 360 version of the game which changes all the landscapes, characters and items to resemble the sci-fi action adventure game series, Mass Effect.

“It’s been a great team effort and everyone worked really closely,” says Roger Carpenter, Minecraft’s Xbox producer. “Much kudos must go to Mojang for being open to the idea and Bioware for letting us play with their IP too – there’s been lots of input from all sides. It has been a long time in the planning but we wanted to offer something familiar yet new to Xbox; to add new aspects and grow the concept.

“A complete takeover of the game with another game is something that we all really loved the idea of and what 4J Studios has created shows considerable care and attention to detail to both games. Mass Effect was perfect for the first outing, a very rich visual style and importantly distinctive to the standard Minecraft look with a rich back-story on which players can fuel their creative sides.”

New Mash-Ups are expected to follow, and Carpenter says the next has already been developed. I know my sons will enjoy them, even though they don’t know Mass Effect – it’s just a new landscape to explore. To them it’ll be like switching from regular city Lego to space Lego.

This is the point. Everything is about personal creativity. You want to build a scale replica of the USS Voyager? Sure, why not?

Minecraft’s biggest audience is the under-16s and Zac’s enthusiasm for the world has taught me why. Minecraft and everything in it is theirs; it bends – unlike so much else in their lives – to their will. When I play Minecraft with Zac he gets to explain to me the vagaries and complexities of his saved kingdoms – the traps he has built, the hidden boltholes beneath looming mountains, the crops he has planted, the eggs he has nurtured, the places he goes, the things he sees. For children the world is still a flexible, plastic construct, and then the dogma and sense of adulthood drains in. Minecraft is at that psychological cusp, that liminal zone between imagination and reality, between revery and action. It has its own physical laws, its own stability, but for the player, the rules merely help structure the imaginative process. Everything is yours.

Other games have come and gone. We’ve been through and enjoyed all the Lego adventures; right now Zac and Albie love Disney Infinity, which provides its own slightly more dictatorial toy box mode. But like millions of others, Zac always returns to Minecraft. Its blocky landscapes – which are minimal yet no less picturesque in their own way – present limitless possibilities to him. In our darker moments as parents, we wonder how much the real world will ever offer him in terms of opportunity and control. Like us, Minecraft knows that he is funny and imaginative and wonderful. Will others?

For now, all is fine, and this game is something he’ll come back to whenever we let him, I suspect for many years to come. In lots of ways that I’m sure will sound familiar to many thousands of fans, Minecraft is like returning home where he feels safe.

Read Original Article Here:

by Stone Marshall | Nov 28, 2014 | Minecraft News |

What is Minecraft? It’s a game, obviously: one that its developer Mojang has sold nearly 54m copies of across computers, consoles and mobile devices so far.

It’s a series of books published by Egmont that sold more than 1.3m copies in the UK alone in the first eight months of 2014. It’s a range of Lego kits that have been selling out rapidly, as well as the source for a line of plush toys, hoodies and other products sold from Mojang’s online store.

But Minecraft is also an educational tool in schools through the MinecraftEdu initiative, and the driver for Block by Block, a partnership with the United Nations Human Settlements Programme to get young people involved in planning public urban spaces, starting with a pilot in Kenya.

Minecraft is also one of YouTube’s most popular video categories – right up there with music – fuelling hugely popular channels like Stampy (the fourth biggest YouTube channel in the world in August with 217.9m views) and The Diamond Minecart (sixth with 190.6m views).

Oh, and at some point in the next 3-4 years, Minecraft will also be a movie, courtesy of a deal between Mojang and Hollywood studio Warner Brothers.

It’s unsurprisingly one of the key topics for nosy questions when The Guardian interviews Mojang’s chief operating officer Vu Bui, ahead of his keynote speech this week at London’s Brand Licensing Europe conference.

A Minecraft film? When’s it coming out? “I still have no idea. A long time. I’m going to guess three years, but it could be four, probably not two. 3-4 years seems to be a reasonable bet,” says Bui, stressing that the project remains in its early days of development.

In February, news site Deadline provided initial details, suggesting that the Minecraft movie would be live-action, and produced by Roy Lee and Jill Messick – Lee having previously produced The Lego Movie, which should bode well.

Advertisement

“We were approached by so many studios, but after talking to Warner Bros, we decided that this are absolutely the team we want to work with,” says Bui. “They respect the brand, respect the IP, and want to make something that is going to be awesome, not just capitalise on the success of the game.”

Is it really live-action? Who’s in it? Bui chuckles as he parries the question. “A movie takes years, especially a large-budget movie like this. It’s still in the beginning stages, and there really isn’t a clear picture yet of what this is going to be. Once there is, I’m sure we’ll share more.”

He’s very clear on one point though: whatever story the Minecraft movie tells, it will just be one story among many possible, matching the way there is no single ‘right’ way to play Minecraft as a game.

“We don’t want any story that we make, whether it’s a movie or a book, to create some sort of ‘this is the official Minecraft, this is how you play the game’ thing. That would discourage all the players who don’t play in that way,” says Bui. “When coming up with a story, we want to make sure it is just a story within Minecraft, as opposed to the story within Minecraft.”

There are plenty of other things to talk about when it comes to the business around Minecraft, which Bui says is still overseen by a tiny core team within Mojang – mainly art director Markus ‘Junkboy’ Toivonen and director of fun Lydia Winters. Yes, that is her job title.

“Every product that exists out there officially, they have gone over pixel-by-pixel, and for the books, page-by-page. We keep all our approvals in-house – we don’t use any licensing agents – and we are very hardcore about those approvals, to make sure each product is something we believe in,” says Bui.

Earlier this year, Angry Birds maker Rovio revealed that 47% of its income in 2013 came from its consumer products division. Minecraft products may be selling well, but for Mojang, the emphasis in its business is still firmly tilted in favour of gaming.

“Licensing is a small portion of our business, and we want to keep it that way. We’re a games studio, and I don’t think that’s going to change any time soon,” says Bui.

“But people do want to have something physical in their life when they’re not in front of a screen. When we make merchandise, we’re thinking about making something for the people who want it and love it, not just as a source of revenues.”

Mojang’s partnership with Egmont has been positive for both companies, but particularly the latter – and the wider children’s books market.

In an appearance at a conference in July, the publisher’s international CEO Rob McMenemy told the audience that in the UK “the children’s book market year-on-year grew by 11%” in 2013. When asked why, he gave a one-word answer: “Minecraft”.

The first four Minecraft books have sold well, in part because they provide some of the tutorial content – from fighting to building – that isn’t in the game itself (even if it is available online as part of the official Minecraft Wiki). The next book, Blockopedia, is a hexagonal-shaped tome exploring individual blocks from the game.

“We didn’t want to make standard-type annuals with graphics all over the cover and every page a Where’s Waldo? Those type of things we weren’t interested in. We wanted to make it valuable: something that people would buy and treasure, instead of simply flipping through then tossing aside,” says Bui.

“If you see the initial pages before our input, and the final product, it’s literally night and day. As a book publisher, Egmont were very concerned with things like the covers: that they look like a more mature book that wouldn’t fit the target audience. But we don’t have a target audience, we don’t look to a particular demographic.

“We have younger people playing on mobile up to people on their 70s and 80s playing with their grandchildren. Yes, most of our customers are skewed towards the younger ages, but people of all ages can enjoy and appreciate them. The books stand out on the shelves, and we’re proud of that.”

Minecraft as a brand isn’t just about commercial products. Bui is just as enthusiastic about MinecraftEdu, citing a stat that’s been circulating internally that 1m students have used it in schools.

“It’s pretty exciting that a game is being used by teachers not just as a reward – do your classwork then you can play Minecraft for 15 minutes – but actually as an educational tool, with teachers developing a curriculum within the game,” he says.

“It’s very interesting to think that in the future, there will be architects and city planners and all these types of people who grew up using Minecraft, and who’ll be applying those skills in ways that change the world.”

The era of skyscrapers with chickens embedded in the walls beckons. But Block by Block shows the seriousness of Mojang’s intent to find out how Minecraft really can be used by people to take more of a role in urban planning: a bridge between citizens and professional architects, rather than trying to replace the latter.

“We’ve got people in slum areas, many of whom have never used a computer, learning how to use Minecraft to have an input into the redesign and reconstruction of public spaces. It’s beyond being a game, to being used as a layman’s architectural tool,” says Bui.

“Then the architect comes in and turns that into what can actually be built. You need that architect still! But previously there wasn’t a good way for local stakeholders to communicate with architects: they didn’t speak the same language. Now that communication can be done through Minecraft.

The conversation turns back to licensing, but not the big partnerships with the likes of Lego, Egmont and Warner Bros. How about people within the Minecraft community making and sharing… well, not necessarily products, but things: from knitted toys to birthday cakes? How does Mojang work with them?

“We want people to be creative, and we are working on ways to help people to that. We have something coming out soon – in the next month or so hopefully – that will clarify what people can do with the brand,” says Bui.

“It’s really amazing what people are doing out there. What’s not interesting to me is when people just take our existing graphics, slap them onto another product and sell it. There’s no reason those products should be out there. But our approach has always been soft: we talk to people and say ‘hey, this isn’t cool’ or ‘hey, this would be cool if you changed it in that way…’”

It will be interesting to see how those new guidelines continue this softly-softly approach to brand protection. With Mojang in the process of being bought by Microsoft for $2.5bn, any misstep is likely to be brandished as evidence of a culture change under the new ownership, even if Microsoft has nothing to do with it.

An interesting point: Bui says the guiding light behind Mojang’s policies is its desire to encourage creativity. “We get a number of emails a week asking if someone can get the licence for Minecraft birthday supplies: plates and hats and streamers,” he says.

“But if you do a Google search for ‘Minecraft birthday’ you’ll see all kinds of creativity from families who went out to the store, didn’t find Minecraft stuff, and so created it themselves. Why would we want to put out the official Minecraft cake-topper then, when the game is all about creativity?

“Once you put out the official one, people would buy it because it’d be easier than making it themselves. We’re more interested in what people make for themselves: it’s way more exciting for us to have people sitting together and having ideas for Minecraft parties, rather than us just selling some cheesy Minecraft products.”

The last topic the Guardian discusses with Bui is Minecraft videos on YouTube, from the hugely-popular channels like Stampy and The Diamond Minecart to the videos uploaded by fans of all ages showing their exploits in the game.

Bui says that Mojang’s approach to YouTube was defined very early on by the game’s creator, Notch, who ensured that people could use Minecraft assets, sounds and gameplay footage on YouTube without having to ask permission or share any of the resulting advertising revenues.

Earlier in 2014, Nintendo was criticised for filing copyright claims against some YouTubers uploading “Let’s Play” videos of its games, inserting its own ads, which left the video creators unable to earn money from their work. Nintendo said it was working on an affiliate program to share revenues with YouTubers, but its approach was still compared – often negatively – with Mojang’s hands-off policy.

“We have a whole slew of people who are making their entire living just off making videos about Minecraft. Just the economics of that – how many people are making a living off this one IP – is pretty awesome,” says Bui.

“That doesn’t take anything away from us, and I would say it actually adds value to Minecraft, to have people who are extremely talented and creative doing things. We’ve essentially outsourced YouTube videos to a community of millions of people, and what they come up with is more creative than anything we could make ourselves.”

There are limits: Mojang’s rule is that uploading videos to YouTube is fine, but selling them on iTunes or other video-on-demand services is not – the key being whether creators are charging fans.

“There’s no damage to us from YouTube. We might have some people who make content we might not agree with, but this is how the democratisation of media works. You put it out there and let the community decide,” says Bui. “If someone’s putting out rubbish, the community is not going to watch it, and it won’t rise to the top.”

The sheer scale of Minecraft as a brand, a community and a cultural touchpoint means Mojang won’t always be able to avoid criticism and online backlashes over the way it manages the game.

A recent controversy over how players can and can’t make money from the Minecraft servers that they run is the latest proof of that. Even so, Bui says that Mojang’s desire to retain its focus as a games studio, as well as its respect for the community around Minecraft, will serve it well.

“As I said, we want to make most of our money from selling games. We’re not here to penny-pinch the creatives out there using our property to create cool content,” he says. “We have this massive group of people creating amazing things. Why would we want to hinder that in any way?”

Read Original Article Here:

by Stone Marshall | Nov 27, 2014 | Minecraft News |

Children and adults alike aren’t just playing Minecraft in their millions: they’re watching YouTube videos made using Minecraft – and those videos are racking up billions of views.

Now online video firm Octoly has published a report aiming to quantify that, claiming that by June 2014, Minecraft videos had been watched 30.8 billion times, with only 183 million of those views coming from the channel of Mojang, the game’s publisher.

That’s nearly three times the total views for videos about Grand Theft Auto, which Octoly estimated was the second most popular gaming brand on YouTube with nearly 12 billion views, ahead of Call of Duty (10.2 billion), Angry Birds (six billion) and Halo (4.8 billion).

The company claims that since June, Minecraft videos have been watched another 16 billion times, taking its total to 47 billion views. “In June, our Octoly360 system found 81,000 separate YouTube creators talking about Minecraft,” explained Octoly. “Today there are 147,000 creator channels with Minecraft videos, almost double.”

Minecraft being so far ahead of rival brands will not come as a surprise to anyone who’s been following the game and/or the evolution of YouTube over the last couple of years.

In a chart of the top 100 YouTube channels in September 2014 published by industry site Tubefilter, using data from analytics firm OpenSlate, child-friendly Minecraft channel Stampy was the third biggest channel in the world with 189.6 million views that month.

Also popular that month were channels with a heavy or total Minecraft focus including Vegetta (eighth in the world with 164 million views in September) and The Diamond Minecart (10th with 161.8 million).

Mojang has supported its YouTube community since the early days of Minecraft, avoiding copyright arguments with video creators, and taking a hands-off approach to the content of their videos.

Advertisement

“We have a whole slew of people who are making their entire living just off making videos about Minecraft. Just the economics of that – how many people are making a living off this one IP – is pretty awesome,” Mojang’s chief operating officer Vu Bui told the Guardian in October.

“That doesn’t take anything away from us, and I would say it actually adds value to Minecraft, to have people who are extremely talented and creative doing things. We’ve essentially outsourced YouTube videos to a community of millions of people, and what they come up with is more creative than anything we could make ourselves.”

YouTube is a big part of the reason why Minecraft is such a strong, well-loved gaming brand in 2014 – and it’s also a notable factor in Microsoft’s decision to buy Mojang for $2.5bn this summer.

Microsoft isn’t just buying a popular game that’s sold more than 54m copies across computer, console and mobile: it’s buying one of the world’s biggest television brands. Despite the fact that it’s huge popularity is online, rather than on traditional television.

Read Original Article Here: